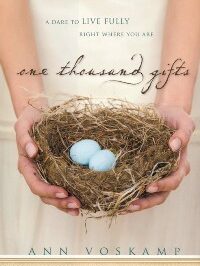

blogger Ann Voskamp invites readers into her world. Through sharing her

personal moments of grace, we learn how to process loss, embrace a lifestyle of

gratitude, and take the time to see God in all the moments of our lives.

“How,” Voskamp wondered, “do we find joy in the

midst of deadlines, debt, drama and daily duties? What does a life of gratitude

look like when your days are gritty, long and sometimes dark? What is God

providing here and now?”

She shares what she learned from asking these

questions and offers readers a guide to living a life of joy.

The Buzz features an excerpt from Voskamp’s new book.

An Emptier, Fuller Life

A glowing sun-orb fills an August sky the day

this story begins, the day I am born, the day I begin to live.

And I fill my mother’s tearing ring of

fire with my body emerging, virgin lungs searing with air of this earth and I

enter the world like every person born enters the world: with clenched fists.

From the diameter of her fullness, I

empty her out—and she bleeds. Vernix-creased and squalling, I am held to the

light.

Then they name me.

Could a name be any shorter? Three letters

without even the flourish of an e. Ann, a trio of curves and lines.

It means “full of grace.”

I haven’t been.

What does it mean to live full of grace? To

live fully alive?

They wash my pasty skin and I breathe and

I flail. I flail.

For decades, a life, I continue to flail

and strive and come up so seemingly … empty. I haven’t lived up to my

christening.

Maybe in those first few years my life

slowly opened, curled like cupped hands, a receptacle open to the gifts God

gives. But of those years, I have no memories. They say memory jolts awake with

trauma’s electricity. That would be the year I turned four. The year when blood

pooled and my sister died and I, all of us, snapped shut to grace.

Standing at the side porch window,

watching my parents’ stunned bending, I wonder if my mother had held me in

those natal moments of naming like she held my sister in death.

In November light, I see my mother and

father sitting on the back porch step rocking her swaddled body in their arms.

I press my face to the kitchen window, the cold glass, and watch them, watch

their lips move, not with sleep prayers, but with pleas for waking, whole and

miraculous. It does not come. The police do. They fill out reports. Blood seeps

through that blanket bound. I see that too, even now.

Memory’s surge burns deep.

That staining of her blood scorches me,

but less than the blister of seeing her uncovered, lying there. She had only

toddled into the farm lane, wandering after a cat, and I can see the delivery

truck driver sitting at the kitchen table, his head in his hands, and I

remember how he sobbed that he had never seen her. But I still see her, and I

cannot forget. Her body, fragile and small, crushed by a truck’s load in our

farmyard, blood soaking into the thirsty, track-beaten earth. That’s the moment

the cosmos shifted, shattering any cupping of hands. I can still hear my

mother’s witnessing-scream, see my father’s eyes shot white through.

My parents don’t press charges and they

are farmers and they keep trying to breathe, keep the body moving to keep the

soul from atrophying. Mama cries when she strings out the laundry. She holds my

youngest baby sister, a mere 3 weeks old, to the breast, and I can’t imagine

how a woman only weeks fragile from the birth of her fourth child witnesses the

blood-on-gravel death of her third child and she leaks milk for the babe and

she leaks grief for the buried daughter. Dad tells us a thousand times the

story after dinner, how her eyes were water-clear and without shores, how she

held his neck when she hugged him and held on for dear life. We accept the day

of her death as an accident. But an act allowed by God?

For years, my sister flashes through my

nights, her body crumpled on gravel. Sometimes in dreams, I cradle her in the

quilt Mama made for her, pale green with the hand-embroidered Humpty Dumpty and

Little Bo Peep, and she’s safely cocooned. I await her unfurling and the

rebirth. Instead the earth opens wide and swallows her up.

At the grave’s precipice, our feet scuff

dirt, and chunks of the firmament fall away. A clod of dirt hits the casket,

shatters. Shatters over my little sister with the white-blonde hair, the little

sister who teased me and laughed; and the way she’d throw her head back and

laugh, her milk-white cheeks dimpled right through with happiness, and I’d

scoop close all her belly-giggling life. They lay her gravestone flat into the

earth, a black granite slab engraved with no dates, only the five letters of

her name. Aimee. It means “loved one.” How she was. We had loved her. And with

the laying of her gravestone, the closing up of her deathbed, so closed our

lives.

Closed to any notion of grace.

Really, when you bury a child—or when you

just simply get up every day and live life raw—you murmur the question

soundlessly. No one hears. Can there be a good God? A God who graces

with good gifts when a crib lies empty through long nights, and bugs burrow

through coffins? Where is God, really? How can He be good when babies

die, and marriages implode, and dreams blow away, dust in the wind? Where is

grace bestowed when cancer gnaws and loneliness aches and nameless places in us

soundlessly die, break off without reason, erode away. Where hides this joy of

the Lord, this God who fills the earth with good things, and how do I fully

live when life is full of hurt ? How do I wake up to joy and grace and beauty

and all that is the fullest life when I must stay numb to losses and crushed

dreams and all that empties me out?

My family—my dad, my mama, my brother and

youngest sister—for years, we all silently ask these questions. For years, we

come up empty. And over the years, we fill again—with estrangement. We live

with our hands clenched tight. What God once gave us on a day in November

slashed deep. Who risks again?

Years later, I sit at one end of our

brown plaid couch, my dad stretched out along its length. Worn from a day

driving tractor, the sun beating and the wind blowing, he asks me to stroke his

hair. I stroke from that cowlick of his and back, his hair ringed from the line

of his cap. He closes his eyes. I ask questions that I never would if looking

into them.

“Did you ever used to go to church? Like

a long time ago, Dad?” Two neighboring families take turns picking me up, a

Bible in hand and a dress ironed straight, for church services on Sunday

mornings. Dad works.

“Yeah, as a kid I went. Your grandmother

had us go every Sunday, after milking was done. That was important to her.”

I keep my eyes on his dark strands of

hair running through my fingers. I knead out tangles.

“But it’s not important to you now?” The

words barely whispered, hang.

He pushes up his plaid sleeves, shifts

his head, his eyes still closed. “Oh … ”

I wait, hands combing, waiting for him to

find the words for those feelings that don’t fit neatly into the stiff ties,

the starched collars, of sentences.

“No, I guess not anymore. When Aimee

died, I was done with all of that.”

Scenes blast. I close my eyes; reel.

“And, if there really is anybody up

there, they sure were asleep at the wheel that day.”

I don’t say anything. The lump in my

throat burns, this ember. I just stroke his hair. I try to sooth his pain. He

finds more feelings. He stuffs them into words.

“Why let a beautiful little girl die such

a senseless, needless death? And she didn’t just die. She was killed.”

That word twists his face. I want to hold

him till it doesn’t hurt, make it all go away. His eyes remain closed, but he’s

shaking his head now, remembering all there was to say no to that hideous

November day that branded our lives.

Dad says nothing more. That shake of the

head says it all, expresses our closed hands, our bruised, shaking fists. No.

No benevolent Being, no grace, no meaning to it all. My dad, a good farmer who

loved his daughter the way only eyes can rightly express, he rarely said all

that; only sometimes, when he’d close his eyes and ask me to stroke away the

day between the fingers. But these aren’t things you need to say anyways. Like

all beliefs, you simply live them.

We did.

No, God.

No God.

Is this the toxic air of the world, this

atmosphere we inhale, burning into our lungs, this No, God? No, God,

we won’t take what You give. No, God, Your plans are a gutted, bleeding mess

and I didn’t sign up for this and You really thought I’d go for this? No, God,

this is ugly and this is a mess and can’t You get anything right and just haul

all this pain out of here and I’ll take it from here, thanks. And God? Thanks

for nothing. Isn’t this the human inheritance, the legacy of the Garden?

I wake and put the feet to the plank

floors, and I believe the serpent’s hissing lie, the repeating refrain of his

campaign through the ages: God isn’t good. It’s the cornerstone of his

movement. That God withholds good from His children, that God does not

genuinely, fully, love us.

Doubting God’s goodness, distrusting His

intent, discontented with what He’s given, we desire … I have desired … more.

The fullest life.

I look across farm fields. The rest of

the garden simply isn’t enough. It will never be enough. God said humanity was not

to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. And I moan that God has

ripped away what I wanted. No, what I needed. Though I can hardly whisper it, I

live as though He stole what I consider rightly mine: happiest children,

marriage of unending bliss, long, content, death-defying days. I look in the

mirror, and if I’m fearlessly blunt—what I have, who I am, where I am, how I

am, what I’ve got—?this simply isn’t enough. That forked tongue darts and daily

I live the doubt, look at my reflection, and ask: Does God really love me? If

He truly, deeply loves me, why does He withhold that which I believe will fully

nourish me? Why do I live in this sense of rejection, of less than, of pain?

Does He not want me to be happy?

From all of our beginnings, we keep

reliving the Garden story.

Satan, he wanted more. More power, more

glory. Ultimately, in his essence, Satan is an ingrate. And he sinks his venom

into the heart of Eden. Satan’s sin becomes the first sin of all humanity: the

sin of ingratitude. Adam and Eve are, simply, painfully, ungrateful for

what God gave.

Isn’t that the catalyst of all my sins?

Our fall was, has always been, and always

will be, that we aren’t satisfied in God and what He gives. We hunger for

something more, something other.

Standing before that tree, laden with

fruit withheld, we listen to Evil’s murmur, “In the day you eat from it your

eyes will be opened” (Gen. 3:5, NASB). But in the beginning, our eyes were

already open. Our sight was perfect. Our vision let us see a world spilling

with goodness. Our eyes fell on nothing but the glory of God. We saw God as He

truly is: good. But we were lured by the deception that there was more to a

full life, there was more to see. And, true, there was more to see: the

ugliness we hadn’t beheld, the sinfulness we hadn’t witnessed, the loss we

hadn’t known.

We eat. And, in an instant, we are blind.

No longer do we see God as one we can trust. No longer do we perceive Him as

wholly good. No longer do we observe all of the remaining paradise.

We eat. And, in an instant, we see.

Everywhere we look, we see a world of lack, a universe of loss, a cosmos of

scarcity and injustice.

We are hungry. We eat. We are filled …

and emptied.

And still, we look

at the fruit and see only the material means to fill our emptiness. We don’t

see the material world for what it is meant to be: as the means to communion

with God.

We look and swell with the ache of a

broken, battered planet, what we ascribe as the negligent work of an

indifferent Creator (if we even think there is one). Do we ever think of this

busted-up place as the result of us ingrates, unsatisfied, we who punctured it

all with a bite? The fruit’s poison has infected the whole of humanity. Me.

I say no to what He’s given. I thirst for some roborant, some elixir, to

relieve the anguish of what I’ve believed: God isn’t good. God doesn’t love me.

If I’m ruthlessly honest, I may have said

yes to God, yes to Christianity, but really, I have lived the no. I have.

Infected by that Eden mouthful, the retina of my soul develops macular holes of

blackness. From my own beginning, my sister’s death tears a hole in the canvas

of the world.

Losses do that. One life-loss can infect

the whole of a life. Like a rash that wears through our days, our sight becomes

peppered with black voids. Now everywhere we look, we only see all that isn’t:

holes, lack, deficiency.

In our plain country church on the edge

of that hayfield enclosed by an old cedar split-rail fence, once a week on

Sunday, my soul’s macular holes spontaneously heal. In that church with the

wooden cross nailed to the wall facing the country road, there God seems

obvious. Close. Bibles lie open. The sanctuary fills with the worship of wives

with babies in arms, farmers done with chores early, their hair slicked down.

The communion table spread with the emblems, that singular cup and loaf, that

table that restores relationship. I remember. Here I remember love and the

cross and a body, and I am grafted in and held and made whole. All’s upright.

There, alongside Claude Martin and Ann Van den Boogaard and John Weiler and

Marion Schefter and genteel Mrs. Leary, even the likes of me can see.

But the rest of the week, the days I live

in the glaring harshness of an abrasive world? Complete loss of central vision.

Everywhere, a world pocked with scarcity.

I hunger for filling in a world that is

starved.

But from that Garden beginning, God has

had a different purpose for us. His intent, since He bent low and breathed His

life into the dust of our lungs, since He kissed us into being, has never been

to slyly orchestrate our ruin. And yet, I have found it: He does have

surprising, secret purposes. I open a Bible, and His plans, startling, lie

there barefaced. It’s hard to believe it, when I read it, and I have to come

back to it many times, feel long across those words, make sure they are real.

His love letter forever silences any doubts: “His secret purpose framed from

the very beginning [is] to bring us to our full glory” (1 Cor. 2:7, NEB).

He means to rename us—to return us to our true names, our truest selves. He

means to heal our soul holes. From the very beginning, that Eden beginning,

that has always been and always is, to this day, His secret purpose—our return

to our full glory. Appalling—that He would! Us, unworthy. And yet

since we took a bite out of the fruit and tore into our own souls, that drain

hole where joy seeps away, God’s had this wild secretive plan. He means to

fill us with glory again. With glory and grace.

Grace,

it means “favor,” from the Latin gratia. It connotes a free readiness. A

free and ready favor. That’s grace. It is one thing to choose to take the grace

offered at the cross. But to choose to live as one filling with His

grace? Choosing to fill with all that He freely gives and fully

live—?with glory and grace and God?

I know it but I don’t want to: It is a

choice. Living with losses, I may choose to still say yes. Choose to say yes to

what He freely gives. Could I live that—the choice to open the hands to

freely receive whatever God gives? If I don’t, I am still making a choice.

The choice not to.

The day I met my brother-in-law at the

back door, looking for his brother, looking like his brother, is the day I see

it clear as a full moon rising bright over January snow, that choice, saying

yes or no to God’s graces, is the linchpin of it all, of everything.

My brother-in-law, he’s just marking

time, since Farmer Husband’s made a quick run to the hardware store. He’s

talking about soil temperature and weather forecasts. I lean up against the

door frame. The dog lies down at my feet.

John shrugs his

shoulders, looks out across our wheat field. “Farmers, we think we control so

much, do so much right to make a crop. And when you are farming,” he turns back

toward me, “you are faced with it every day. You control so little. Really.

It’s God who decides it all. Not us.” He slips his big Dutch hands into frayed

pockets, smiles easily. “It’s all good.”

I nod, almost say something about him

just leaving that new water tank in the back shed for now instead of waiting

any longer for Farmer Husband to show up. But I catch his eyes and I know I

have to ask. Tentatively, eyes fixed on his, I venture back into that place I

rarely go.

“How do you know that, John? Deep down,

how do you know that it really is all good? That God is good?

That you can say yes—?to whatever He gives?” I know the story of the man I am

asking, and he knows mine. His eyes linger. I know he’s remembering the story

too.

New Year’s Day. He asks us to come. Only

if we want. I don’t want to think why, but we know. “Already?” I search my

husband’s face. “Today?” He takes my hand and doesn’t let go. Not when we slide

into the truck, not when we drive the back roads, not when we climb the empty

stairwell to the hospital room lit only by a dim lamp. John meets us at the

door. He nods. His eyes smile brave. The singular tear that slips down his

cheek carves something out of me.

“Tiff just noticed Dietrich had started

breathing a bit heavier this afternoon. And yeah, when we brought him in, they

said his lung had collapsed. It will just be a matter of hours. Like it was at

the end for Austin.” His firstborn, Austin, had died of the same genetic

disease only 18 months prior. He was about to bury his second son in less than

two years.

I can’t look into

that sadness wearing a smile anymore. I look at the floor, polished tiles

blurring, running. It had only been a year and six months before that. The

peonies had been in full bloom when we had stood in a country cemetery watching

a cloud of balloons float up and into clear blue over pastures. All the

bobbing, buoyant hopes for Austin?—?floating ?away. Austin had hardly been 4

months old. I had been there on that muggy June afternoon. I had stood by the

fan humming in their farm kitchen. The fan stirred a happy-face balloon over

Austin’s placid body. I remember the blue of his eyes, mirrors of heaven. He

never moved. His eyes moved me. I had caressed my nephew’s bare little tummy.

His chest had heaved for the air. And heaved less … and less.

How do you keep breathing when the lungs

under your fingers are slowly atrophying?

I had stumbled out their back steps, laid

down on the grass. I had cried at the sky. It was our wedding anniversary. I

always remember the date, his eyes.

And now, New Year’s Day, again with John,

Tiffany, but now with their second-born son, Dietrich. He’s only 5 months old.

He was born to hope and prayers—?and the exact same terminal diagnosis as his

brother, Austin.

John hands me a Kleenex, and I try to

wipe away all this gut-wrenching pain. He tries too, with words soft and steady,

“We’re just blessed. Up until today Dietrich’s had no pain. We have good

memories of a happy Christmas. That’s more than we had with Austin.” All the

tiles on the floor run fluid. My chest hurts. “Tiffany’s got lots and lots of

pictures. And we had five months with him.”

I shouldn’t, but I do. I look up. Into

all his hardly tamed grief. I feel wild. His eyes shimmer tears, this dazed

bewilderment, and his stoic smile cuts me right through. I see his chin quiver.

In that moment I forget the rules of this Dutch family of reserved emotion. I

grab him by the shoulders and I look straight into those eyes, brimming. And in

this scratchy half whisper, these ragged words choke—?wail. “If it were

up to me” and then the words pound, desperate and hard, “I’d write this

story differently.”

I regret the words as soon as they leave

me. They seem so un-Christian, so unaccepting—?so No, God! I wish I

could take them back, comb out their tangled madness, dress them in their calm

Sunday best. But there they are, released and naked, raw and real, stripped of

any theological cliché, my exposed, serrated howl to the throne room.

“You know” John’s voice breaks into my

memory and his gaze lingers, then turns again toward the waving wheat field.

“Well, even with our boys … I don’t know why that all happened.” He shrugs

again. “But do I have to? … Who knows? I don’t mention it often, but sometimes

I think of that story in the Old Testament. Can’t remember what book, but you

know—when God gave King Hezekiah 15 more years of life? Because he prayed for

it? But if Hezekiah had died when God first intended, Manasseh would never have

been born. And what does the Bible say about Manasseh? Something to the effect

that Manasseh had led the Israelites to do even more evil than all the heathen

nations around Israel. Think of all the evil that would have been avoided if

Hezekiah had died earlier, before Manasseh was born. I am not saying anything,

either way, about anything.”

He’s watching that sea of green rolling

in winds. Then it comes slow, in a low, quiet voice that I have to strain to

hear.

“Just that maybe … maybe you don’t want

to change the story, because you don’t know what a different ending holds.”

The words I choked out that dying, ending

day, echo. Pierce. There’s a reason I am not writing the story and God is. He

knows how it all works out, where it all leads, what it all means.

I don’t.

His eyes return, knowing the past I’ve

lived, a bit of my nightmares. “Maybe … I guess … it’s accepting there are

things we simply don’t understand. But He does.”

And I see. At least a bit more. When we

find ourselves groping along, famished for more, we can choose. When we are

despairing, we can choose to live as Israelites gathering manna. For 40 long

years, God’s people daily eat manna—?a substance whose name literally means

“What is it?” Hungry, they choose to gather up that which is baffling. They

fill on that which has no meaning. More than 14,600 days they take their daily

nourishment from that which they don’t comprehend. They find soul-filling in

the inexplicable.

They eat the mystery.

They eat the mystery.

And the mystery, that which made no

sense, is “like wafers of honey” on the lips.

A pickup drives into the lane. I watch

from the window, two brothers meeting, talking, then hand gestures mirroring

each other. I think of buried babies and broken, weeping fathers over graves,

and a world pocked with pain, and all the mysteries I have refused, refused,

to let nourish me. If it were my daughter, my son? Would I really choose the manna?

I only tremble, wonder. With memories of gravestones, of combing fingers

through tangled hair, I wonder too … if the rent in the canvas of our life

backdrop, the losses that puncture our world, our own emptiness, might actually

become places to see.

To see through to God.

That that which tears open our souls,

those holes that splatter our sight, may actually become the thin, open places

to see through the mess of this place to the heart-aching beauty beyond. To

Him. To the God whom we endlessly crave.

Maybe so.

But how? How do we choose to allow the

holes to become seeing-through-to-God places? To more-God places?

How do I give up resentment for

gratitude, gnawing anger for spilling joy? Self-focus for God-communion.

To fully live—?to live full of grace and

joy and all that is beauty eternal. It is possible, wildly.

I now see and testify.

So this story—?my story.

A dare to an emptier, fuller life.

Click here to purchase One Thousand Gifts.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.