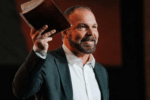

Putty Putman may have attended a Vineyard church, but this quantum physics grad student couldn’t have believed less in the gifts of the Spirit. Then a mission trip to China radically transformed his life and forced him to confront the supernatural reality of our world.

Today Putman leads the School of Kingdom Ministry, which trains and equips believers of all ages and backgrounds to live out the gifts of the Spirit in their community. He spoke to Charisma about his incredible testimony, how Millennials and Generation Z approach the Holy Spirit differently than previous generations, and three common misunderstandings Christians have about the gifts of the Spirit.

This interview—originally recorded for our New Year, New Voices podcast series—has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the full interview here:

Berglund: What’s your testimony?

Putman: I grew up in the church. My dad worked for a Baptist denomination since shortly before I was born until about two years ago, when he retired. So a lot of my testimony is framed around the fact that I have never not known Jesus, as long as my memory goes back.

I grew up in the church. I love the church. I always had a real walk with God that was really significant for my life. But a lot of my journey was around coming to meet the Holy Spirit. I got a lot of wonderful things out of that upbringing: real value for the Scriptures, for the church, for fellowship in the body, things like that. But what I didn’t get a lot of was exposure to the ministry of the Holy Spirit. I knew He was real, but I never really understood what He did.

So I had this wonderful upbringing. I considered ministry when I was choosing career paths, but I honestly never saw a pastor who seemed really happy. They always seemed like their job was really heavy and hard. It didn’t seem like they were having any fun. So I didn’t head toward ministry. I headed into the sciences. Turns out I was or I am very gifted in the area of physics especially.

When I say that, a lot of people kind of get a little stunned, and they must think I’m superhuman or something. Just to speak into that: I’m really good at physics. I’m not great at everything else. But for some reason, I’m very good at physics.

So I got my undergraduate degree in physics. After completing undergrad, I chose to go and get a Ph.D. That was how I came to the community I’m in right now, Champaign-Urbana in central Illinois. I came here to get a Ph.D.—in quantum physics of all things—at the University of Illinois. When I got here, I immediately thought, OK, graduate student in the sciences? Not exactly an environment conducive toward faith. I need to get plugged in to a faith community.

I had some friends down here who were studying, and they were plugged in with this goofy church that I’d never heard of called the Vineyard Church. I showed up. The first day was kind of an interesting church experience. Everybody is warm. Everybody is kind. The worship is a little more expressive than I’m used to, but, you know, I can live with all that. The message is fine.

But at the end of the service, the young adult pastor pops up on the stage and says, ‘Hey, here at the Vineyard, we believe God is still real and that God still heals. Our prayer team met beforehand, and here’s some things that we felt like God had brought to mind.’ He starts listing off these words of knowledge and conditions that could be happening in people’s lives. He essentially closes by saying, ‘Hey, if any of this is going on with you, I’d just like to invite you to come up. We have a prayer team that would love to minister to you. Who knows? You may even see God heal you today.’

Now I am coming from my Baptist framework, where I’ve never seen any of this. And coming from that Baptist framework—where I assumed I knew everything, because part of being a Baptist is assuming you know everything—I thought, Who are these people? And what have I stumbled into here? These people are crazy. I was very closed. I was not open to this at all. I was pretty judgmental. Not my thing.

So what wound up happening is since I had enough invested in graduate school, and I already had some friends at this church, I decided, ‘I’ll keep attending this church. I don’t have to get on board with the crazy, but I need something that keeps me connected to the body and building my journey of faith.’ So I sat at this church for four years, really judging just about every single service because I’m not on board with all of this Holy Spirit stuff.

What winds up happening is over time, being in that environment, I did see that in the Bible, there’s more of a value for things like healing than I had first acknowledged. Jesus does a lot of miracles, and the Gospel writers seem to really care. They don’t just say ‘Jesus healed a lot of people.’ They go into these painstaking accounts. Sometimes they’ll just be like, ‘Jesus taught a lot. But then He did this miracle…’ and they’ll go into great detail about that miracle. I wrestled with that and came to the conclusion, OK, this stuff seems to matter to Jesus. But I don’t know about this expression of this, and this church feels weird.

After four years of being an evangelical fish in a charismatic pond, what happened was God essentially cornered me, and I wound up going on a mission trip to China. Our church had started a partnership with house churches in China, where we [would] go train and equip local believers. I was really excited about that, because when I was young, about 7, we had spent a year living in China as missionaries. It was a very formative experience, and I had always wanted to go back.

So when our church started this partnership, I said, “Oh, I’ve got to go get signed up for the trip.” I got the plane ticket and bought all the supplies. It’s only after all of that do I learn that the purpose of this trip is to go train these Chinese churches in healing ministry. I thought, Oh, do we have to do that? Can’t we go build a hut or a well, or do some sort of other mission work? But nevertheless, this was the trip. I’d already committed to go. I’d already spent money.

So I worked out this deal with the trip leader. I said, “Here’s the deal. I’ll participate, but when it comes to all the prayer stuff, that’s on you guys. That’s not really my thing.”

She says, “OK, that’s fine. We can do that.” We struck this deal. So the day the training came, during the first part, the team is sitting there, listening for words of knowledge, and I’m just twiddling my thumbs like, I made the deal. This isn’t my thing. I’m waiting for the clock to run out.

Meanwhile, my left forearm starts feeling very odd. It’s a very distinct sensation. I wasn’t feeling that earlier, and I didn’t know if I’d felt that before. As I paid attention to it, I realized the feeling was on the inside of my arm, like right between the two bones and your forearm—right in the core of the arm.

I didn’t know you could feel something there, and it is distinctly getting stronger, I thought. This is a very weird experience.

While I’m having this experience, I remembered attending a prayer training class three weeks earlier—I knew we were going to go teach it, so I figured I should at least be familiar with the material even if I didn’t believe in it. I remembered in the class they had mentioned this thing called “sympathy pains,” which I just thought was the silliest thing: “That’s absolutely crazy.” But the idea of a sympathy pain is where you feel something in your own body that’s a mirror image of what’s happening in someone else’s body. It’s a way to get one of these words of knowledge.

So I thought, Hmm. I’m having this weird experience. This idea of sympathy pain is sort of coming back to mind. I’m in China. … Whatever, I’ll throw it out. If there’s anything to it, the team will deal with it.

So the time for listening concluded and I share, “Does somebody have a left forearm condition?”

We’re sitting in a room with about a dozen house church leaders. This isn’t like a massive audience. Up until this point, most of what I’d seen modeled are words of knowledge with rather large crowds, and what I’d mostly seen is kind of generic words of knowledge with large crowds. You know, I’d see a room of 300 people and someone on stage say, ‘Someone here has knee pain or back pain.’ Like, OK, as a physicist, I know there are a dozen people in this room with knee pain. That’s just playing the odds. That’s statistics. You don’t need the Lord to say it to know there’s someone in this room with lower back pain. I mean, 1 in 5 people over 40 has lower back pain.

So I had processed words of knowledge from a very naturalistic paradigm, but in a room where there’s 12 people and I’m calling out “left forearm,” all of that goes right out the window. I couldn’t name another person anywhere who had a left forearm condition, and we were in a room of 12. One woman responds to this word. So I was processing all this as a physicist, not as a pastor, and trying to think through the odds of this.

Meanwhile, the team leader wrapped up conversing in Chinese with all the people there and says, “OK, Putty. It’s time for you to come up.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

She says, “Well, you got the word of knowledge, so you lead the prayer time.”

I forgot that’s what they do at the Vineyard. I should have known that. I’d seen them do that a ton of times. But I just kind of blanked on it. Now I’m the “expert missionary who came from America” who got the word of knowledge, and they’re all thinking I’m some expert. Whereas internally, I know I don’t even believe in this stuff.

Truth be told, I just decided, It’s not like I’ve really seen this thing work at home anyway. I can just fake it, and it will be OK. I’m just telling you how it was. I thought, OK, I’ve seen how they do this. You ask a couple of questions about the condition and you put your hand on their shoulder. You invite the Holy Spirit to come. Then you pray for a little bit. And then you try and encourage the person because nothing happened. That’s what I’d seen play out a bunch of times at church. So I asked some questions, put my hand on her shoulder, and invited the Holy Spirit to come.

When I do, basically He showed up and blew the whole room apart.

The first thing that happened is the presence of God comes crashing through the ceiling of the hotel room right above this woman and drops on her with what felt to me like the force of a waterfall. It wasn’t this kind, gentle, “Oh, I feel God’s peace” or something. She just buckles and drops straight to the floor in a heap. Not forward. Not backward. She just collapses and drops straight down. As that happens, the rest of the room stands in a circle around us watching, and about half of them I hear gasp collectively around me as the presence of God enters the room. I hear thud, thud, thud, thud, thud. People start falling in every direction.

In basically 10 seconds, we went from classroom to war zone. I looked around, and there were people on the ground. They were rolling; they were shaking; they were snotting; they were crying. I look behind me, and there’s someone who’s dry heaving into a trash can. I didn’t even know what that meant! And I just thought, What on earth is happening? This is absolutely crazy. I don’t believe in any of this stuff. I don’t do this stuff.

I turned back and looked at the girl. My hand is still on her shoulder. She’s now sitting kind of roughly cross-legged on the floor. I look at her, and she’s kind of twisting and contorting, and making all kinds of weird faces and saying all kinds of things in Chinese that I can’t understand but I can clearly see aren’t positive sentiments. I asked the team leader, “What is she doing?”

The team leader says, “Oh, it’s a demon.”

“What’s the demon?”

The team leader said, “she’s manifesting a demon right now.”

I think, Oh my goodness. I have no idea what to do here. The one class I took, which I didn’t even believe in, never mentioned demons. I’m so far in over my head. What on earth do I do?

It really looked like I knew how to do this, but I had no idea what I’m doing. I’m racking my brain, and as I think about it, the thing that comes to mind for me is that, being raised Baptist, I spent a lot of time in Awana and spent a lot of time in the Word. I knew Jesus had driven out demons. So what did He do? The only thing I could think of is He commanded them to come out, so I started commanding the demon, “Come out of her in Jesus’ name.”

It doesn’t respond immediately. She would become lucid, but then when you commanded the demon to come out, she would snarl at you. Then eventually we’d get her lucid again, and you’d command the demon out, and it was this back-and-forth thing. It was really mind-boggling to me.

Eventually, after probably 45 minutes—it wasn’t quick—she shuddered and said, “Whoa. Something just happened.”

We asked, “What happened?”

She said, “It left.”

“Well, be specific,” I said. “What left?”

She said, “I felt this dark presence over my life that hung over my life like a cloud all the time. And it just left. It’s gone.”

I said, “Well, check out your wrist.”

She rolls her wrist around, and says, “My wrist feels great. I think I’m healed.”

So everybody got up off the floor, and there were about a million questions—you know, because it’s training, and all of this has just happened. Everybody’s telling me, “I need help processing this,” and I’m like, “You don’t understand. I need more help processing this than any of you. I have more questions than anybody else.”

That became a turning point in my life. Suffice it to say, there were a lot of things I had to adjust in terms of how I understood the world and God in the more than 10 years since. After that, I defended my thesis, graduated and got my degree. I was faced in my own personal life with a choice: I could choose to continue in physics, or I could choose to be part of what God was doing here at our local church—but in my situation, I couldn’t really have both. I’m not saying others couldn’t; that’s just how it worked for me. So I decided to follow Jesus’ words: Sell all that you have to buy the pearl and get the kingdom.

I stayed here, crash-landed a promising career in physics, and that was the beginning. Eventually I came on staff at the church, and we started this thing called the School of Kingdom Ministry, which does training and equipping in all of this Holy Spirit ministry stuff. God has really breathed on that. It’s just multiplied. Eventually, churches started coming to us, saying, “We want to participate as well. We want to be a part of this thing.” We started it in 2011, and we really opened it up to other churches in 2013. We’re now six years into that; we’ve had classes in 196 different locations, and 7,064 people have been students or leaders—mostly across the U.S. but increasingly around the world.

So what started for me as judging the ministry of the Holy Spirit has actually turned into something I was called to, and I just didn’t even know it. Now what I do is train, equip and release people in the very thing that I sat in the back row and judged for four years. Isn’t that the justice of God for you?

Berglund: It’s funny how God tends to work like that. Even as you’re now describing your experiences then, you clearly have a very rational way of explaining and approaching the supernatural. But of course, supernatural is in many ways “super-rational”—beyond the rational world and fully what we can understand. So how does that work for you when it comes to training and equipping people to operate in the supernatural?

Putman: I love that question. I think you’ve really pegged me and my approach to this. There can be a sentiment in the charismatic church of ‘Shut your brain off. This isn’t supposed to make any sense. Just go with it.’ Part of the reason why I struggled for four years was that I could never do that with integrity.

To be fair, there were some ways in which I was closed—I didn’t want it to be real, because I was afraid of what that meant. But in another way, God has wired me so that I use my mind, and I don’t think that’s a negative thing. For me to embrace practices that I can’t wrap my worldview around, to some extent, is just requiring me not to be me. For me, a big part of my journey has been, How can I see these things without giving up my perspective and the scientific training that I have? Do these things really have to be opposed to one another? I don’t think they do.

I attended undergraduate at Bethel University up in St. Paul, Minnesota. One thing I heard a lot up there which I find very helpful is they would say all truth is God’s truth. All truth belongs to God. Not all truth is in the Bible. All that’s in the Bible is true, but the Bible doesn’t teach about genetics. That’s just not in there. It’s not supposed to address everything. And the truth that we can learn about the world that isn’t in the Bible, it still does belong to God. It’s still God’s truth. So for me, I think that frames the way I approach it.

If people really get healed, then that’s a true thing, and we don’t need to be afraid of thinking about that. We don’t need to be afraid of scientifically testing that. We don’t need to be afraid of examining that with the tools we have. If a prophecy is accurate, then that prophecy is accurate, and it should be demonstrably accurate, not just in a fuzzy, “We’re going to choose to find a way to believe it” kind of way.

If you look at the history, Christians have always been great thinkers. I don’t think being charismatic means we can’t be a good thinker. I mean, look at the apostle Paul: one of the most incredible thinkers of all time, and he sure was charismatic. He found a way to embrace being able to use his mind effectively but also walk in the power of the Holy Spirit. And that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to produce people who have a rounded, theological approach, who understand how ministry in the spirit fits in the broader framework of Christianity.

Berglund: That’s great. At the School of Kingdom Ministry, I’m sure there are people who come to it who aren’t necessarily starting from ground zero, like you did, but rather come because they love the gifts of the Holy Spirit and want to get better at operating in them.

Putman: Absolutely.

Berglund: Among those people, what do you find are the most inaccurate or problematic ideas people can take into the training?

Putman: There are a number of them! The first thing that comes to mind, and I kind of hinted at this earlier, is that we can incorrectly correlate weird and God activity.

Look, when God does something, by definition, it’s going to be weird because He’s transcending the natural order. It’s going to not fit in the “normal.” When God does something, it’s going to be weird. But we don’t need to add weird to God. God has the free range to do whatever He wants. He’s God; we don’t boss Him around.

But there’s a lot that happens that, to me, feels like an attempt to participate in what God’s doing, where what’s actually happening is we’re being weird, hoping that being weird will make God do something. There’s a balance there. Sometimes God does ask you to do something that’s weird, and you have to be willing to go there. But my approach is to start as normal as possible, and let God mix in whatever weird He wants. We don’t need to start weird and then hope that God will breathe on our weird, if that makes sense.

I think that really matters, because my goal is to produce people who can move in the things of the Spirit, in the context of both church and the community outside the church. I want you to be able to get a word of knowledge and pray for healing in the church building or at your home group meeting. But what I really want is for you to be able to prophesy to your neighbor or pray for your family members at the family reunion or minister to someone who’s going through a divorce at your workplace. To me, that’s the holy grail I’m aiming for. If it only stays within the bounds of the church, then in my opinion, we haven’t really aimed ourselves at Jesus’ model.

The majority of Jesus’ miraculous ministry was not done in the synagogue. There were some times—it’s not zero. But a lot of the times Jesus is engaging and ministering out in the midst of society. If we’re not careful, we can create a culture in the church where we correlate weird and God, but then there’s no way for us to bring out the gifts in a way that doesn’t turn people off so much that an unbeliever will say, “You’re being weird. I’m out of here.” We don’t need to add weird to God.

Another thing I regularly see believers lack is a thorough understanding of how all of this Holy Spirit ministry stuff fits within the broader context of salvation and the redemptive story. I’m 1000% for the ministry of the Spirit. But that is a component of Christianity, and we need to understand how that weaves together with the other major components, like: What does it mean to be reconciled in relationship with God? What does it mean to be a new creation? How do those things connect with the idea of being empowered by the Holy Spirit and sent to continue the ministry of the kingdom?

If we don’t understand how those questions weave together, we wind up presenting a partial package. That can result in practitioners that don’t have the ability to go the long haul.

I’ve seen it play out this way many times, where people will come to a conference, and perhaps they’ll get an impartation or just be really inspired: “I’ve got to do this again. I’m going to pray. I’m going to see God do amazing things.” And they lean in, and they go for it for three weeks. And then life catches up with them, and they lose their initial enthusiasm. Before they know it, they’re mostly back to normal life, and hopefully they’ve gained 2% above whatever they had before they went to this conference. To me, that’s the sign of a nonintegrated understanding of how the miraculous and the Holy Spirit are connected to the overall journey of faith.

We see Jesus lead and live an ongoing lifestyle of Holy Spirit and kingdom ministry, where He’s doing this stuff all the time. It is natural and normal for him. He doesn’t need to be psyched up to do it. He doesn’t need to be inspired to do it. It is the natural overflow of the belief system that He has and the walk that He has with the Father. If we don’t come to that point, then we’ll create practitioners who need constant enthusiasm and re-inspiring to keep them doing it, when in reality, it’s supposed to be the normal overflow of our lives. So that’s another piece.

Finally, I believe that partnering with the Holy Spirit is a learnable skill. Now, that doesn’t mean I can do healing or prophecy outside of the leading of the Holy Spirit. He supplies the supernatural juice. But my ability to discern and effectively partner with what He’s doing is a skill that I can develop. When you think about it that way, you wind up approaching learning how to do all of this stuff with a different mentality.

For much of the church, I see a mentality where doing Holy Spirit stuff is approached as a kind of “magic pixie dust” that gets sprinkled on people. Once you get the magic pixie dust sprinkled on you—if you’re so fortunate—all this supernatural stuff just happens. You don’t really know or control how it happens any more than you knew or controlled how it didn’t before you had the magic pixie dust sprinkled on you. The target and goal of this kind of thinking is, “I’ve got to have something I don’t presently have, which will somehow magically make this stuff start working. I won’t understand it when it does, but at least it’ll be working.”

To be clear, I do believe in impartation. I’m not trying to undermine impartation. I think that’s real. I think that matters. But what I find is that most believers have a whole lot more going on with the Holy Spirit than they are tracking and partnering with effectively. God is talking to Christians way more than most of us recognize. The problem is we dismiss His voice. And if we do recognize that it’s Him, we don’t know what to do with it. We don’t know how to act on it. We don’t know how to test it. We don’t know how to actually take that experience, recognize it and convert it into something useful.

God is actually doing a whole lot more through most Christians when they pray than they realize. For a lot of believers, healing actually starts to happen. They just don’t know how to perceive it and partner with it when it does. So they come to conclusions like, “Well, it’s not my gift,” and they assume they can’t do it. My approach is to say, “Hold on. No. Learning how to do what you see the Father doing is a learnable skill. You learn how to see what the Father’s doing, and then you learn how to do what He’s doing. Those are skills that can be developed.”

That means we want to create arenas for practice. We probably want to create feedback loops where people are helping us understand what we’re seeing and what we’re doing and what in that is working and what isn’t. If we’re wise, it involves learning to layer complex skills on top of simple skills, the same way we learn every other skill set. When you learn to play piano, you learn the basic scales before you move up to basic songs before you move up to complicated songs. I think there are actually basic-level skills of partnering with God and then more intermediate and then more advanced; and we can learn to develop all of those so that as the Holy Spirit leads, however He leads, we’re cooperating with a developed skill set, instead of just saying, “God showed up, and something random is going to happen. I guess I’ll do whatever feels natural in the moment. Hopefully it’ll take”—which tends to be the approach I see most people take. I think that’s better than doing nothing. I’m 100% for that. But I want to develop competent practitioners, ones who understand how to recognize the leading of the Holy Spirit and how to partner very effectively.

That results in a model of training and equipping that can at first feel dissonant for people, because they’re expecting the Holy Spirit to move in inherently extremely unpredictable and random and almost chaotic feeling ways. But that’s not an environment that helps people develop skills. The environment that helps people develop skills is a little more structured, intentional and purposeful.

So what we do is we create environments like that. And then we say, “OK, Holy Spirit, would You come and be the teacher? Jesus promised You would come and teach us and guide us into all these things. So here’s a structured environment. Would You come and act as the teacher? Would You show us how to partner with You in this kind of way?” What happens is people actually begin to develop skill sets and become more and more competent practitioners.

Berglund: Obviously, we know that the Holy Spirit doesn’t change. God is unchanging. But from your perspective, have you noticed any differences between how younger and older charismatics engage and interact with the gifts of the Spirit?

Putman: In short, the answer is yes. I definitely have. There are a few different directions I could take this answer.

One would be the understanding of where all of this fits with respect to the journey of faith—and how this meshes with society as a whole. Another would be expectations of where the ministry of the Holy Spirit takes you and what you’re supposed to do with it. And then the third would be different expectations in terms of how that correlates to our connection to the church body. So let me kind of take each of these in turn.

First, let’s talk about my expectations of experiencing the Holy Spirit within the realm of Christianity and how that intersects with society as a whole. I’m a very early Millennial, by my understanding of the generations and their cut-off dates and stuff. I’m 36 right now. What I see is Millennials—and I think Gen Z also is somewhat similar—struggle to embrace something where experience and teaching don’t have a high amount of synthesis.

I didn’t experience the Charismatic Renewal, so I can’t accurately speak to that. But it feels to me that, in previous times, sometimes the gospel could have been thought of as inherently sufficient: “The gospel is good enough. And if you have the Holy Spirit, that’s icing on the cake.” So to speak. I think that kind of thinking doesn’t really fly very well with the younger generations.

I think younger generations are growing up in a far more post-Christian environment, where they’re not going to believe in Jesus simply because it’s the culturally acceptable thing to do. Because it’s not. So where does the rubber meet the road with this? Because if this isn’t experiential, if Christians just want to give them a body of teaching, they’re not really interested in that.

The truth is that all day every day, I already get marketed stuff. On every website, on every social media platform, on every media channel, I’m constantly getting marketed. I don’t need you to market me your idea of what the truth is, too. But if you’re offering something to me, where you can give me a legitimate experience and then help me understand that experience, now we’re talking.

I really see the experience of the Holy Spirit and the ministry of the Spirit being increasingly critical to Christianity as a whole in America. Along with being a post-Christian culture, we’re also increasingly a culture that’s open to other spiritualities. Whether it’s meditation or whatever, there are loads of spiritual practices that are largely embraced by big sectors of culture. And if we are offering a practiceless Christianity where we don’t have experience as a part of the package, we’re going to be looked at as less.

I think that that’s actually a shift. Because 20 to 30 years ago, it was kind of like, “Here’s Christianity. And, oh, by the way, there’s this Holy Spirit experience stuff too, which you’re not expecting, and I’m going to have to sell you on, and you’re going to have to adjust your thinking and be OK with that.” Now it’s sort of like, “Oh, you don’t have spiritual experiences? Then I’m not sure I would even give this a serious glance.” I think the centrality of the ministry of the Spirit, experiencing the inbreaking kingdom, is becoming more and more important.

The second thing is, I think, a good thing and a gift from the Lord. The younger generations are very societally oriented. I care about our culture and society in a different way. I want to know that I’m improving the world that I live in. That doesn’t just mean being part of a church that improves the world I live in. I want to be able to feel I’m making my neighborhood or workplace better. I want to feel a strong connection to that.

What that translates to in Christianity—and particularly Spirit-empowered Christianity—is the younger generation takes more seriously and puts more stock in the idea that the gospel should be transforming our communities, not just great churches and getting people saved. We should be seeing the crime rate in our community drop. We should be seeing the lack of consistent education across different racial barriers go away. We should be seeing societal indicators changing because of the presence of the church in the community doing the kingdom things we’re called to do.

In other words, the proof in the pudding is no longer going to be just in the church walls. If so-and-so got healed and so-and-so got the financial breakthrough we’ve been praying for, that’s great. It needs to be happening in the church. But I think the younger generation is also going to be asking, “How is prophecy helping shape the business sector in our community?” I want to know that. Who’s prophesying to businesses, and how is that helping business break through in our community? Where are words of wisdom speaking into our educational system? How can we partner gifts of healing with our hospitals?”

These are the kinds of things our generation and the younger generations have a lot of passion wrapped around. It’s going to result in having to rethink the purpose of local churches. How do we structure and organize them? What does it mean to be a meaningful member in a local church? In the past, a lot of the “contract” was, “If you’re a part of this local church, then we want you to help build the church.” I think, in time, the contract’s going to change to say, “If you’re a meaningful part of this local church, we expect you to be on mission in our community.” That’s going to be a big shift. Exactly how all that works, I don’t know.

The last thing that I see is we really want to do things together more. Family has almost entirely shattered and broken down communally in the last 50 years. So the majority of us come from, at best, a dysfunctional family, if not a split one. We have a big gap and need in our life for feeling like we’re part of a family. When we come to the church, we don’t want spiritual superheroes that we get inspired by and say, “I’m with that guy” or “I’m with that gal.” We want to feel like we’re a part of a family that has our hands linked together, that’s doing something collectively.

I think that that has implications for our local churches and also the way our local churches relate to one another and pursue ministry in the community together. I think we’re less inclined to get caught up on the doctrinal difference between this church and that church. We’re more like, “All right, do you follow Jesus? Do you believe He’s the only way to get saved? OK, that’s what I’m looking for. Let’s figure out a way to make this place a better place to live.”

I think there’s a kind of togetherness in the church. If I were going to frame it spiritually, I’d say it’s a real spirit of unity. This generation really cares about unity, and I feel like I see God really breathing on it.

Berglund: Regarding the spirit of unity, it seems like among Millennials and Generation Z, there seems to be more openness to the gifts of the Spirit than there was in the past. I don’t know if that’s a result of the breakdown of the denominational barriers you described, and I’m not sure what would be causing that. Is that something that you’ve observed as well?

Putman: Absolutely. I think you’re spot-on with that. I think we’re kind of experientially wired, maybe? It feels to me like the idea of a Christianity that doesn’t have a strong experiential component feels empty—in a way that it doesn’t seem like, say, Generation X or the Baby Boomers felt.

I think the Baby Boomers and Gen X were really on a search for truth. That’s what they wanted. They wanted to know, “Do you have the accurate truth? Are you giving me the real deal? Is it bulletproof? Can I build my life on it?” That really feels to me what those two generations wanted—the Baby Boomers were looking more to the build, and the Gen Z were looking more to the bulletproof.

But when you’re coming to the Millennials and the Generation Zs, we’re looking for a holistic experience of faith that does include truth, but also includes experience, and then puts them at much more equal footing than the previous generations did. The result of that is, for example, when I read the Bible, I see characters doing this healing thing or this prophecy thing. Well, then, I want to have that too. That’s the experience the Bible points to, so I definitely am interested in that.

That’s kind of my hypothesis as to the why—but who knows exactly? I’m not exactly like a societal analyst, but I do sense that.

In the past, it was a real barrier. You were either part of the Holy Spirit crowd or not part of the Holy Spirit crowd. There wasn’t really much of a gray area there, and if you weren’t part of it, you were closed. Now it almost feels like the default is “curiously open.” We’re not really debating, “Are these things real?” We’re asking, “What level of experience do you want? Do you have, and do you want?” Almost everybody takes them as a given. It’s just that some people really want to walk in a lot of the gifts, and some people are OK with the occasional dose. But most everybody seems like they’re more open to it.

Berglund: I have to imagine that’s such a different dichotomy for many of our older readers and listeners, who had to go through the movement’s origins. In those days, like you said, you could be potentially ostracized for believing that the gifts were real.

Putman: You’re exactly right. There was a really big cost. There are a lot of forerunners who paid a heavy price there, which I think is something the younger generations need to keep in mind. We don’t have a price, but they paid a price.

And also, for prior generations who took the cessationist side, there’s a kind of skepticism that lives there. That’s another thing that we need to realize. Just because you’re curiously open to the gifts of the Spirit doesn’t mean your mother or grandmother is, and we shouldn’t judge her for where she came from and the world she lived in, you know? Just like I would hope she wouldn’t judge me for the world I live in. There’s a lot of nuance in all that that I think really matters.

One of the other unities that really matters is the intergenerational unity. I see God just doing that everywhere around the body as well. This is not just like sideways unity; it’s generational, up-down unity. And a real element of that kind of unity is learning how to tackle all that.

—Find Putty Putman on his website, Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.