In New Orleans–home of the wildest street party in the world–brave evangelists disregard the shocking displays of drunkenness and nudity to take Jesus’ love to the boldest of sinners.

The saxophonist sitting against the wall at the end of Bourbon Street, the famed home of New Orleans jazz, squeezes out a mournful version of “Amazing Grace” as the man wearing only a giant diaper and clutching a 64-ounce bottle of beer wanders past. Bystanders seem to ignore both the harmony and the irony. The cops nearby look bored, the tourists amused. Click. Another photo for the album.

A few hours later into the evening, Saxman and Diaper Guy are nowhere to be seen. The musician has given up his busking spot to the crowds that are pouring into the historic French Quarter to celebrate what the city proudly proclaims to be the greatest free party in the world. The partyer’s infantile costume has been eclipsed by more “adult” creations. Leather and bare flesh feature prominently.

Through the years, New Orleans’ famous Mardi Gras has slipped from daringly decadent to downright degenerate. Risqué has given way to raunchy, provocative to pornographic. Locals insist that the suburban parades still retain a family atmosphere, but even Mardi Gras lovers among them admit that the Crescent City carnival’s growing reputation as a sleazy free-for-all celebration of drunkenness and nudity is sadly well deserved.

It is epitomized in the center of Bourbon Street, where young men prowl for video memories of their visit. Swarming around a young woman, they thrust their cameras overhead in an effort to capture her on tape as she bares her breasts in exchange for some of the carnival’s famous plastic beads. The men hoot and cheer and move on to find the next willing exhibitionist.

A woman strips naked from the waist down on a balcony and grinds her hips as the onlookers roar their appreciation. Buttocks-baring leather chaps and bondage harnesses are paraded outside a gay bar. A costumed Elvis poses with fake giant genitals on display. Click. Click. Click.

There’s a strong mixed scent of beer and sweat, spiked with the occasional sickly sweet splash of marijuana. At the curbsides, the partyers kick their way through a growing mound of trash that the city, seemingly unaware of the metaphor, weighs to gauge the size and success of Mardi Gras. Letting the good times roll, as the city’s motto crows, is certainly a messy business.

Majdi does not mind, though. He has driven 1,400 miles with three friends to check out all he has heard about “the city that care forgot,” and he is not disappointed. The New Jersey delivery company operator is having a blunt breast-baring appeal painted onto the back of his bald head before the next round. “Mardi Gras kills anything I have ever seen in New York, even Times Square,” he laughs. “This is by far crazier…it’s just wild. I’m going to tell my grandchildren about it.”

Linsey may not tell hers everything. “It’s a tradition, you know,” says the 20-something Texan of her breast baring. “It’s this thing where you can do it even though it might be morally wrong in other places. It’s like it’s an exception, a tradition…you have to carry it on.” The piles of beads her three male companions are wearing prove she has been successful in this regard, but she has not fared as well with all the free liquor shots being passed out by the bars. “I can’t seem to get drunk for some reason,” she laments.

Inside a little church tucked a street away, where five small rows of pews are squeezed in next door to a corner bar, a woman sighs and declares: “If God doesn’t judge New Orleans, then He’s going to have to apologize to Sodom and Gomorrah.”

She is not alone in her view. Many believe that just as erosion of the Mississippi River’s levees threatens to flood New Orleans in the future, so the steady wearing away of self-restraint is going to end with the city drowning in overflowing decadence if things don’t change.

Which is partly why as well as being the scene of what is the biggest open-air party in the United States, New Orleans also is the rendezvous for the largest ongoing gathering of street evangelists across the country. For around 25 years they have come from many states and even overseas–this year between 1,500 and 2,000 of them–to take the love of Jesus to the streets.

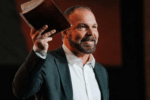

“I have always felt like the devil can generate a crowd, but why don’t we turn it into a congregation,” says veteran street evangelist Scott Hinkle, who has been bringing teams to Mardi Gras for 20 years. “Christian ministries go to great expense in their effort to generate a crowd to preach to people; why not take advantage of the devil’s publicity to communicate the gospel?”

God and Fat Tuesday

Those who have embraced Hinkle’s philosophy are just a drop in the ocean of humanity that brings an estimated $1 billion to New Orleans in Mardi Gras revenue, but they are not hard to spot. Above the raised hands and video cameras on Bourbon Street can be seen a small cluster of crosses down at one of the intersections. Elsewhere banners proclaiming God’s love compete with others selling “Huge A– Beer.”

Like small tide breaks in a swollen river, clusters of Christians stand against the flow of the crowd, passing tracts to the passers-by, trying to engage the revelers in conversation. They get a mixed response from the crowd. Some laugh. Some curse. Some throw beer. Some argue. Some ignore. But some stop to listen, talk–even pray.

At one corner, a weary party girl sobs on the shoulder of a woman, splashing beer from the plastic cup she still holds, as the revelry swirls around her. A couple of streets away a visiting Christian crouches beside a one-too-many reveler as he vomits by a wall.

“The fish are here,” observes Mel Rolls, pastor of Rescue Atlanta, an inner-city church, who wears his enduring love for his hometown on his wrist, in the shape of a Saints watch (“the only football team in the Bible we are told to pray for!”). “You don’t even need to have the right bait,” he says after 17 Mardi Gras outreaches. “You can hook some of them just by reaching out and loving on them.”

Considering most visitors seem to have little more than beer, beads and breasts in mind, a surprising number are open to debate with the evangelists. Hinkle reckons it’s because they have come “looking for the big party, the ultimate blow out–they are coming in a search mode; they are open to new things.”

But the exchanges are not all friendly. Teams have been hosed down and urinated on from balconies. At one intersection a young teen-age girl passing out tracts with her mother hands one to the passenger of a truck making its way slowly through the press of people. He smiles and presses something into her hand in return–a condom.

As Mardi Gras climaxes with the Fat Tuesday celebrations, the collision between holiness and hedonism gets downright ugly. Street preachers with crosses take up their traditional spot outside St. Louis Cathedral at Jackson Square. Tomorrow morning the steps to the Catholic church will be packed with people lining up to have a cross of ashes smudged on their foreheads as a sign of repentance, but right now the doors are locked to visitors.

Led by a man dressed as the pope, swigging from a bottle of red wine, a group of between 20 to 30 hecklers gathers in front of the evangelists. For the next three hours a succession of speakers attempts to share the

gospel amid a barrage of vicious mockery. Some protestors feign sex in front of the podium. Others wearing obscene face masks jump up and down behind the speaker.

“Ah, blasphemy. My favorite form of humor,” purrs a woman dressed as a nurse to her companion, as they pause to watch the standoff. A man walks up beside the preacher and exposes himself, smiling, to a photo-snapping friend. Click.

Some of the demonstrators carry signs like, “Got Nails?,” “Love Your Enemas” and “Ask Me About Satan.” A group performs a pagan ritual nearby, and a naked man dances in front of the Christians before being arrested after his third appearance. It is a rare intervention by authorities, who for the most part turn a blind eye to the nudity and perverse costumes.

Next to the evangelists’ pitch, a giant painting of Christ on the cross is unrolled. Jesus’ face

has been cut out, and a sign overhead invites people to “Crucify Yourself” and put their heads through the gap for a fairground-style photo. Click.

“It is spiritual warfare,” says Brian O’Connell, who unflap-pably holds a cross in the middle of the storm. Dressed as Jesus, he has carried a cross for a decade and is at Mardi Gras for the 11th time. “Where we are standing right now is the heart of evil in the city.”

Seasoned Mardi Gras outreachers believe it is no coincidence that the greatest fury provoked by the faithful is unleashed here, in a sunny, tourist square that is home to artists, street performers–and almost 40 tarot card readers and fortunetellers. They trace what one noted secular historian describes as the “Mardi Gras spirit” back to New Orleans’ interwoven roots as a bastion of Catholicism and America’s voodoo capital.

Mardi Gras is traditionally seen as a religious festival that got hijacked. The French name means “Fat Tuesday,” when the devout indulge in one last good time, one last good meal before entering 40 days of somber Lenten fasting. Many still see it that way–like Christian, who despite his name, doesn’t have much time for the visiting “Jesus Freaks.”

The native New Orleanian is wearing just a face mask and a small loin cloth, and passing out free cups of his homemade “Pantsdown Punch” (“What’s in it? Everything!”) to the crowds. “I don’t think they understand that we’re going to repent,” he says, seriously, of the evangelists. “I’m a Catholic, I’m going to repent. Come on, give us the weekend!”

But beyond church tradition, Mardi Gras also has echoes of ancient fertility rites. Many of the “krewes,” or clubs, that put on the famous parades bear names reflecting Roman, Greek and Egyptian mythology: Bacchus, Orpheus, Babylon and Isis. One guide book records the city “installing Satan as the ruler of Carnival in 1857.” To this day, each Mardi Gras sees the mayor symbolically hand the keys of the city to the King of Carnival.

“It’s a city that prides itself on decadence, very spiritually oppressed,” says Anthony Freeman, president of the New Orleans School of Urban Missions, where students are required to complete two Mardi Gras outreaches before graduating. “It’s a perfect laboratory,” says Freeman, “…one of the greatest training grounds for Christian apologetics.”

“We have to rise to the level of intensity that the devil is,” says Wayne Northup, an enthusiastic young Assemblies of God evangelist who has brought 280 college-age evangelists with him. “Ninety percent of Christians aren’t like that. If we can show these people we are as serious about Jesus as they are about partying, they will say, ‘These people are real; this isn’t just religion.'”

Lynn Chance, a petite single mother from Swainsboro, Georgia, was terrified on her first outreach. Coming from a sheltered background she was “overwhelmed–the nudity, the homosexuality.” First time out on the streets she was approached by a man who shouted, “I’m Satan, and I am going to kill you.”

She recalled: “I looked at him, and I said, ‘I want to go home.'” But other team members prayed with her and encouraged her to stay–and she found new courage. Now she is back for the fifth time. “It makes me a wild woman,” she says.

Raising a Moral Standard

If through the years Mardi Gras has become “an unofficial soul-winners’ convention,” as Hinkle puts it, then one of the main agenda items is methodology. While many evangelists major on God’s love, a number trumpet His judgment. One giant banner lists “rebellious women,” “child molesting homosexuals” and “wimpy Christians” among those who “spiritually stink.” Another declares: “Turn to Jesus or burn in hell.”

Under a 70-pound banner proclaiming “Know the God of the Bible,” Reuben Chavez from Los Angeles admits he is “an in-your-face kind of guy.” Through the years he has been beaten, pushed, threatened and even arrested for disturbing the peace (“At Mardi Gras?” he observes.) “People say we’re turning them off,” he says. “I’m saying they have never been turned on. I give the sermon needed. You don’t give eulogies at weddings.”

Frank King, a seasoned street preacher, puts it this way: “You have to preach them lost to preach them saved; you have to get them to realize that they won’t get into heaven on their grandmother’s apron strings.”

Meanwhile, Hinkle reminds his teams that the gospel message may be offensive to people, but as messengers they don’t need to be. “While there’s a place to deal with sin and the penalty of it, I believe that the harder the message, the more broken the heart ought to be of the one who is preaching it,” he tells them.

In a water break from the streets at a nearby church, one participant defends the hard-hitting evangelists. “I call them the scrub nurse preachers,” he says. “Scrub nurses have to clean the wound before the doctors can sew it up. There’s a lot of pus in the church–people preaching mercy without the judgment of God.”

As the visiting Christians arrive, many local believers actually head out of town. Churches routinely take advantage of the public holiday to organize getaway retreats and arrange special events to keep their young people from being tempted to go to the French Quarter. Very few take part in the outreach.

“I’m thankful they come,” says Frank Bailey, pastor of Victory Fellowship, of the Christian visitors. “When you live in this atmosphere day after day you can become almost apathetic toward Mardi Gras and lose your sense of how really terrible it is. It’s almost like a shock back to reality; there’s a reason they are coming here.”

Gregory Pembo has been known to confront the more extreme Mardi Gras partyers and tell them: “You are in my neighborhood now. Go home.” Former owner of a wine store located across the street from a Baptist church, he has pastored a hole-in-the-wall Assemblies of God congregation just down the street for the last 10 years. He wonders what Mardi Gras might be without the evangelist teams. “They are a restraining influence,” he believes. “They raise a moral standard.”

But how many see it? Copycat Mardi Gras celebrations, some marred by ugly violence, have sprung up across the country. Some New Orleanians proudly point to the absence of similar problems in their city as a sort of seal of approval for its long-established casting off restraint.

After the event, the leader of one of the larger outreach groups will estimate that, through everyone’s efforts, maybe 1,000 people have prayed to receive Christ in New Orleans this year–just about one person for every two tons of garbage left behind.

But those like King don’t doubt the value of the outreach. The former biker and pimp with 92 tattoos and prison time for gang crime says that it saved his life–and that of another. The 46-year-old was on the run when he arrived in New Orleans for Mardi Gras in 1989.

Dirty, homeless and desperate, he had been thinking of suicide when someone bought him a beer and said he had a job for him. King was on his way to meet the man again–who, he discovered later, was going to ask him to kill someone (“I’d have done it, too. I was desperate”)–when he bumped into a visiting evangelist.

Freed from the grip of sex, drugs and alcohol, he now pastors a small church in Elkhart, Indiana, and returns to Mardi Gras every year “partly to return what God has given me.”

He adds: “I raised a lot of hell. I want to lower a lot more heaven.”

When the Party’s Over

Mardi Gras celebrations come and go, but Billy Seibert runs a year-round outreach in New Orleans’ famous French Quarter.

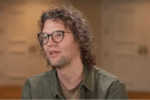

More than one visitor to New Orleans’ bohemian French Quarter has done a double take when passing Billy Seibert on the street. The long-haired, tattooed Vietnam vet bears a striking resemblance to the late Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia, who for many still epitomizes the carefree spirit of the city featured in the 1960s’ protest movie, Easy Rider.

But while Seibert spends most of his time in the coffee bars and streets where performance artists and tarot card readers vie for tourists’ attention and dollars, he is not a hippy throwback searching for answers–but an evangelist looking for questions.

Seibert is the founder of Street Level Inc., a radical outreach to the picturesque French Quarter. While hundreds of street evangelists come to New Orleans each year to reach the thousands of visitors to raucous Mardi Gras, Seibert and his team concentrate on the residents who call the colorful area home year-round.

There are street entertainers, avant-garde artists and nightclub performers. The district also has a large gay community, which stages its own annual Decadence Week. Far from being your typical suburban neighborhood, the alternative culture population requires a low-key ministry approach, Seibert says.

“We don’t do tracts; we don’t use bullhorns,” he says. “We believe that you reason with people; you don’t argue with them. We move in, hang out, build relationships and just try to be friends to people, show them the love of Christ through the people we are.

“Once you have started to earn someone’s trust, then you can share where you are coming from. Usually we wait for them to ask us. If someone asks, ‘What are you into?’ I say, ‘Jesus is ultimate truth,’ and I stop there. I do a lot of listening and not a lot of talking, until they ask the questions–then I’m very up front and honest, but I don’t push it.”

Billy and his wife, Brenda, moved into the French Quarter eight years ago. Their current apartment home is actually on celebrated Bourbon Street. Saved in 1969, they divorced when he backslid and fell into drugs and alcohol, but they later remarried. He worked as a mental health counselor before starting a house church and ministry to bikers through a tattoo shop. When the couple sold everything to start the French Quarter ministry–initially through Youth With a Mission, then independently as Street Level–the bikers took up an offering to help them on their way.

Much of Seibert’s time is spent trying to overcome people’s negative views of Christianity. “They see it as being an exclusive religion because they say, ‘You say there is only one way to God,’ and that upsets them. The reason is because they want to be able to sin and still think they can come to God.”

Maggie, one of the Seibert’s three grown children, is part of the Street Level team with her husband, Dale. She is the only heterosexual employee at the local postal emporium, but has won the friendship of her co-workers.

When the young couple found they were expecting a baby, they took the sonogram picture of their unborn child in, and Maggie’s colleagues hung the picture up on the wall. The baby “became ‘the postal emporium baby,'” Billy says. “One employee I spoke with said, ‘I am a pro-choice person, but seeing Maggie makes me not like that position.'”

The exchange sums up Seibert’s sensitive approach, captured in Street Level’s scriptural motto, “Come let us reason together,” taken from Isaiah 1:18.

“I think that Christians who tell someone they are going to hell are starting from the wrong premise,” he says. “I don’t believe you will convert anybody by threatening them. The way you treat people shows Christ so much more than yelling at them.”

Andy Butcher is editor of Charisma News Service and senior writer for Charisma. In May he received the Evangelical Press Association’s first-place award for best reporting for his article about the world’s street children (“Listen to the Children Crying,” June 2000).

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.