One year ago this month, Operation Allied Force ceased it bombing campaign in the Yugoslav region. Charisma interviewed pastors in this war-ravaged land to learn how Gos is still at work in the aftermath of unthinkable violence.

One year after the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia to crush President Slobodan Milosevic’s murderous purge of ethnic Albanians, the tense political balance in this part of the Balkan Peninsula is being shaken by new destructive forces–ones that moved in after the bombers flew home and the guns fell silent.

Like air being sucked in by a vacuum, desperation and hopelessness have rushed into the hearts of the people, occupying a void carved by the warfare of 1999 and smothering spirits already scarred by a decade of civil war and widespread social upheaval.

Yet for the Serbs, Hungarians, Romanians, Gypsies, Kosovo-Albanians, Montenegrins and other ethnic groups who live within the borders of what many call Europe’s “most hated country,” the years of ruin are creating a new spiritual vacuum as well.

Pentecostal leaders in the country say there is an emptiness in the people that is driving many of them into churches–where they have been reluctant to go in the past. This is pressing them into the arms of God–where they are finding fresh hope and new life amid the loss so many of them share in common.

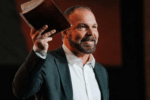

“During the Bosnian war 10 years ago, the poorest groups came to our churches to receive help, but most of them left as soon as the financial situation improved,” says Viktor Sabo, a Pentecostal pastor and church-planter in the city of Senta in northeast Yugoslavia and the missions director of the National Pentecostal Movement.

“In the last year–after the Kosovo war and the NATO bombings–educated people and entrepreneurs have been coming because now even they have lost all hope. They do not come to the church for food–but out of desperation.”

Some Yugoslavians who once lived in high-income comfort, or even luxury, are intently seeking God after being left with virtually nothing after the war. Many of them, in particular businessmen who had hoped for Western economic aid to develop their country, were left empty-handed when NATO bombers wasted whatever infrastructure and industry there was.

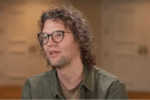

Aleksandar Mitrovic, a Pentecostal pastor in Novi Sad and a leading Christian intellectual on the Balkans, told Charisma that the social and political situation in Yugoslavia is “worse than ever” after the NATO campaign and “very dangerous with regard to the future.”

“The older generation has lost all hope, the middle-aged are beaming with anger and frustration, and the young–seeing no future–resort to more or less criminal quick-money schemes,” he says.

Sabo’s church in Senta represents one small haven in which the compassion of God is restoring hope to some of those who lost everything during the war. Individuals and families, the young and the old–all with a different story of hardship, yet all desperately in need of rebuilding their lives, are finding sanctuary in God’s love through Sabo’s church.

One of his church members from northern Yugoslavia inherited a successful business from his father. He soon lost some of it, and after trying his luck with one of the many pyramid schemes that ruined hundreds of thousands of people in the Balkans during the 1990s, he lost it all.

His family had to leave their fancy house with a pool and step down from luxury to lack. Yet, as Sabo points out, the war in Kosovo last year gave the family what it truly was lacking.

“Starting with Grandma, the whole family found their way to our church,” he told Charisma. “They are earnestly seeking God’s ways now and will soon be baptized.”

Another well-to-do family from the south panicked last spring when the bombs started falling and sold all their property at a great loss. They came to Senta with two suitcases and moved in with a relative, before ending up at Sabo’s church.

“Now they have nothing–no job, no apartment,” Sabo says. “Their relative wants to get rid of them. Someone invited them to our church, and they also will be baptized soon.”

In addition, more teen-agers and children than ever before come to Sabo’s church–some with and some without their parents. The church sanctuary and all adjacent rooms are filled to capacity every weekend, and the Pentecostal congregation will need more space soon.

“Unfortunately, we are not well-prepared to receive the young,” Sabo admits. “At our meetings we praise and preach, and that is not enough.” Because teen-agers want fellowship and camaraderie, explains Sabo, his Senta church hopes to start a club for teens in the center of the city sometime soon.

Many newlywed couples are seeking fellowship in the church as well, and the current church cell group for young families in Senta has opened its doors for unbelievers. “We are learning ourselves [how to minister], but already many churches in the country have asked for our help in opening up to the young,” Sabo says.

Fighting to Survive

Despite the new growth and interest at Sabo’s church, the actual number of people involved is minimal because–as Sabo points out–membership in Yugoslav churches is rarely high.

“In Senta, church attendance has doubled–from 50 to 100,” he explains.

In all of Yugoslavia, with a population of about 11 million, there are some 7,000 believers, most of them Pentecostal. With the exception of the Pentecostal Gypsy Fellowship in Leskovac in south Yugoslavia, which numbers 1,000-1,500 people, and the Pentecostal Church in the capital city of Belgrade, which numbers 500-700 members, congregations rarely exceed 100 members throughout the country.

That is true in Kikinda, which is close to Senta; in Podgorica, capital of the state of Montenegro; and in other places where Yugoslav churches are experiencing growth. Still, the nationwide desperation that remains after the NATO bombings makes Sabo hope that revival is imminent.

“People have nothing left to hope for,” he states.

Pastor Mitrovic of Novi Sad views the situation in much the same way. The positive aspect of this crisis–at least for Christians, he points out–is that it “favors discipling.”

“Christians either backslide or grow fast,” Mitrovic explains, “because on top of the everyday hardships of life in this country, you are hardly willing to face the additional pressure of being harassed or even persecuted as a charismatic Christian unless you commit yourself wholeheartedly to Jesus.”

Yugoslavia is an Eastern Orthodox country, and the Orthodox Church–assuming an extreme nationalistic position–is lobbying to outlaw charismatic Christianity while portraying charismatics in the government media as “Western agents and traitors to the Serbian cause.”

The Pentecostal church in Novi Sad has not grown in numbers in the last year, but Mitrovic states that “many believers have matured, and there is a much stronger commitment to prayer and fasting.” He sees in his own church as well as in others around the country a “new openness to work with God rather than for Him.”

Contrasting the hope being offered by the country’s small body of Pentecostal believers is a national isolationism caused by war that has cut the country off internationally and built distrust among its people for political leaders. Across Yugoslavia the international community is viewed as an enemy and no longer seen as a potential partner.

Within, few Yugoslavians trust the chief of state, President Milosevic, and opposition to him is divided and weak. Though national elections are scheduled for later this year, many observers expect them to be postponed, and it is unlikely that Milosevic will be ousted from the seat he’s held since July 1997.

Civil freedom in Yugoslavia is severely restricted as well. The police are omnipresent, both in the cities and the countryside. Church leaders told Charisma that their telephone wires are tapped and e-mail is monitored.

A year after the war in Kosovo, very few factories have resumed work, disabling a labor force that is about 40 percent industrial workers. Even small businesses that require fewer resources to be operational–such as print shops, garages, and carpentry and plumbing businesses–are crippled by the lack of money in circulation. The inflation rate on consumer prices is estimated at 48 percent.

As one Christian photographer who works in Senta put it: “With just a few dinar in their pockets, people cannot buy anything but food.”

A minor part of the workforce–some say 20 percent–is employed, and even those workers receive their payment irregularly. A high school teacher in Senta told Charisma she received her January salary at the end of March and that she considers herself fortunate.

One newly married man in Ada, in the north, has been without a job since last summer. His wife had their first baby in September. The couple is entitled to monthly government support to cover both his unemployment and child care, but in April they had not yet received a single dinar.

In Novi Sad, Gordana and Stefan Maksimovic, the wife and youngest child of Goran Maksimovic, who directs the city’s Pentecostal Bible School, are both suffering from terminal hepatitis B and are in urgent need of treatment. With the medical cost amounting to $6,000–roughly the equivalent of 12 years’ worth of net pay for a high school teacher in Yugoslavia–the public health service has declined even to start the therapy.

Demand for health care is increasing in Yugoslavia. According to Goran Maksimovic, the hospital in Novi Sad is treating twice as many cancer patients as a year ago, and doctors blame the increase on exposure to depleted uranium used in some NATO bombs.

The black market, traditionally an important source of income in the Balkans, is expanding faster than ever. The U.S. government claims the region is a major trans-shipment point for Asian heroin being moved into western Europe. Church leaders told Charisma that authorities hesitate to stop black-market trade because high-ranking government officials are involved, and closing the market down would deprive many people of their only income and trigger a humanitarian catastrophe.

The situation in southern Yugoslavia–around Kosovo–is worse than in the north. The southern population, mostly Serbs and Gypsies, is much poorer historically. They now have even less to eat and feel more desperate. Anti-Western sentiments are running high after the NATO bombings, and there are very few churches.

An Opportunity for the Gospel

Despite Yugoslavia’s pressing everyday needs and its gloomy prospects for the future, Sabo emphasizes that it is time for all Yugoslav Christians to start giving. The pastor and church-planter plans to tour all Pentecostal churches in the country during the year to mobilize believers for national and international church-planting endeavors.

“There are many young Christians in our churches with great potential,” Sabo told Charisma. “It would be a waste of resources not to train and send them. My goal for this year is to find 10 young pastors willing to commit themselves to pioneer work within Yugoslavia or the Serbian part of Bosnia.”

The Yugoslav church, however, also needs a global vision, Sabo says. He stresses to young Yugoslav Christians that they should look toward the world’s developing countries for opportunities to minister. He believes that “the rich West presents too big a temptation to young Yugoslavs.”

He says this without overlooking the fact that Yugoslav churches themselves are in dire need of financial and spiritual support, especially from Christians in Western countries. The isolationism carried over from the war that depresses the economy and morale of the nation is limiting the resources and influence of the church as well.

“We are dependent upon the financial giving of churches in the West,” Sabo says, “but we also need more contacts. The isolation we are living under is hard to bear. Friends visit from time to time, but very few [of them are] church and mission leaders.

“I hope for more partnerships–Western churches linking up with two or three Yugoslav churches on the basis of friendship,” he adds.

Sabo notes that many Yugoslav pastors have not been out of the country for years–if ever–and would love the chance “to visit brothers and sisters in other countries.”

Mitrovic underscores the need for this, saying that in the long term the loss of social objectives and social responsibility in Yugoslavia is devastating for the nation. Because people struggle to survive and need help on a daily basis, he says, the Yugoslav church faces hard decisions. Its priority, he believes, must be on long-term changes.

“We cannot feed the people today even if we focus on it, but we can take the lead in the spiritual and ethical revolution that would enable Yugoslavs to feed themselves tomorrow,” Mitrovic says. “It is our job to give to the nation the hope that would release people’s creativity and energy.”

He states flatly that stereotyped forms of evangelism will not help accomplish this goal because they won’t work with the needs that people currently face.

“In Yugoslavia it takes more than telling people that Jesus loves them. We have to speak up publicly against all forms of unrighteousness and discrimination in our society, using the media,” he says.

Evangelical Christians currently are nearly invisible in the public eye, but Mitrovic believes it would be possible, in spite of the political oppression, to print newspapers and books, to cover the cities with evangelistic tracts and to broadcast on private radio. He is urging fellow church leaders in Yugoslavia, as well as international supporters, to rechannel existing resources because there is too much investment in programs that neither further church growth nor make an impact on society.

The ongoing social and political crisis that continues to shake Yugoslavia represents a strategic opportunity for the Yugoslav church to spread the gospel. The desperation and hopelessness that occupy the land mean there is no neutral ground for the church.

According to Mitrovic, the country’s Christians must choose either to become a prophetic voice–providing the nation with answers taken from the Scriptures–or become an integrated part of the Yugoslav tragedy.

“The church must become God’s holy book to this nation,” he says. “If we live the message, we can fill the present vacuum. If we don’t, someone else will.”

Tomas Dixon is a journalist based in Sweden. He has filed reports for Charisma from Macedonia, Italy, Turkey, Israel and Austria.

Peacemakers in Bosnia

Civil war has torn Bosnians apart, but Pentecostals here are demonstrating how rival nationalities can find hope together.

After 10 years of war, the co-inhabitants of the former Yugoslavia–Serbs, Croats, Slovenians, Bosnians, Macedonians, Albanians and others–are separated by new borders, and by NATO and United Nations military personnel. The hatred and the bitterness are deep, and all parties agree that if the international forces were withdrawn there would be a another vicious war.

Pentecostals in Bosnia, however, are demonstrating that even in the aftermath of the Balkans’ ethnic wars, peace can exist among God’s people, regardless of nationality. Among the new Pentecostal churches in Bosnia that were planted during the war in the early and mid-1990s, the three major ethnic groups in the country share an existence without strife.

Karmelo Kresonja–pastor of West Mostar Pentecostal Church, the largest Bosnian church–told Charisma that there are “no ethnic tensions whatsoever” between the believers: converted Catholic Croat-Bosnians, Orthodox Serb-Bosnians and Muslim Bosnians. In the East Mostar Church there are even 30 Kosovo-Albanian believers, refugees from last year’s strife in Kosovo between Serbs and ethnic Albanians.

“Outside our churches the unforgiveness and hatred are as strong now as five years ago,” Kresonja says. “The European Union thought that if they rebuilt the houses, the Bosnians would move together again, but people would rather leave the country than return to live with their former neighbors. Everything in Bosnia is still ethnically divided.”

The Christian testimony is unique–but minuscule.

“Bosnia has some 4 million inhabitants, and we total some 300 baptized believers,” Kresonja told Charisma. “After the miraculous beginnings in the midst of war–when five churches were planted with one-third Croats, one-third Serbs and one-third converted Muslims–we have not grown in numbers.” Still, he adds, they could plant new churches immediately “if only there were more nationals willing to commit.”

Bosnia is one nation divided into two administrative divisions: the Serbian Republic and the Muslim-Croat Federation. Only the Muslims have any leaning toward multiethnicity.

Originally the Bosnian Muslims were Serbs or Croats whose historical forefathers converted to Islam to improve their standing with the then-Turkish rulers. Generally they were never religiously zealous. Although they developed an identity of their own that was influenced by the Turkish-Muslim culture, it was never as strong as the Catholic identity of the Croats and the Orthodox identity of the Serbs.

Bane Erceg, a Bosnian Serb who pastors two church plants in the Serbian part of Bosnia, told Charisma that reconciliation is still far off. The Bosnian Serbs prefer staying in refugee camps rather than returning to their former houses in Muslim or Croatian areas.

“People here wish for an open border with Yugoslavia–that is, Serbia–and would prefer the ‘border’ with the Croatian-Muslim part of Bosnia to be stronger,” Erceg says.

There are now a handful of small churches planted in the Serbian republic in Bosnia, the biggest one numbering about 40 people. They are linked with the Yugoslav (Serbian) Pentecostal Churches, not with the Bosnian churches. At a pastors’ conference held in Budapest, Hungary, in April, Kresonja, Erceg and Enver Redzic–a converted Muslim Bosnian–hugged, prayed for and blessed one another.

“We have started to discuss how to face our diverging realities,” Erceg told Charisma. “On the one hand we belong to one country–Bosnia. On the other hand the people groups we deal with see each other as enemies.”

Erceg said he is in favor of closer relationships with the churches in the Croat-Muslim part of Bosnia but that he also needs strong links with the Serbian churches in Yugoslavia. “We need Christian books using the Cyrillic [Russian] alphabet, and these books we get in Serbia,” he says.

Pentecostal believers in Bosnia face the same restrictions and harassments as they do in Yugoslavia. Pentecostals are viewed more or less as dangerous sects both by the Catholic Bosnian Croats and the Orthodox Bosnian Serbs. Erceg has been trying unsuccessfully to rent a central meeting place.

“As soon as the landlords hear that I am a Pentecostal Christian, they turn me down,” he says. “Ironically, there is more freedom here for Catholics and Muslims than for us.”

Still, says Erceg, Bosnian believers move forward, limited to spreading the gospel in private homes or evangelizing one-on-one in public.

Yugoslavia’s Long Conflict

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

(Serbia and Montenegro)

Only Serbia and Montenegro remain today as a self-declared federal republic under the name Yugoslavia. The other republics–Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, and Slovenia–declared their independence in 1991 and 1992. The U.S. government does not formally recognize the union of Serbia and Montenegro as Yugoslavia.

Population:11.2 million

Ethnic groups:Serbs 63%; Albanians 14%; Montenegrins 6%; Hungarians 4%; Others 13%

Religions:Orthodox 65%; Muslim 19%; Roman Catholic 4%; Protestant 1%; Other 11%

Government type:republic

Head of state:President Slobodan Milosevic (since July 1997)

Capitals:Belgrade (Serbia); Podgorica (Montenegro)

Official language:Serbian

Economy:Currency: Yugoslav new dinar. Sanctions exclude Belgrade from international financial institutions and a ban on investments and a freeze on assets imposed in 1998 because of the government’s military actions in Kosovo have multiplied economic woes.

Recent history: With the demise of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989, the Yugoslav republics of Serbia and Montenegro voted for communist governments while their sister republics of Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina sought independence. A vicious civil war resulted, and Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic sought to keep all ethnically Serbian areas under Serbian control. The civil wars ended in 1996 with Milosevic endorsing treaties guaranteeing the boundaries of Macedonia, Croatia and Bosnia. In 1998, ethnic Albanians in the Kosovo province of Serbia attempted to secede and join Albania. The Milosevic government intervened with genocidal warfare, which was stopped by the NATO bombings against Serbian forces last year.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.